Golf’s New World Order, Part 5: Golf and the Future

In Part 5 of this series about the developments in pro golf in the summer of 2022, I offer some possible forecasts for golf's future by sifting through the evidence of sport's past.

In Part 1 of this essay series, I went through the history of the PGA Tour’s business model, the troubled present, and what the new business of the LIV Tour might look like. Part 2 considered the geopolitical moment, in particular the possible decline of the United States as the dominant global superpower and the aspirations of Saudi Arabia to use its oil riches to rise the international political ladder. Part 3 was all about the practice of sportswashing, which the Saudis’ strategic investments are are often accused of. Part 4 considered some of the reasons that players—some of them who could still expect many lucrative years ahead of them on the established tour—might have decided to leave, and considered how a century of developments in psychological science might tell us something of their motiviations.

This is Part 5: Golf and the Future.

Golf and the Future

Earlier in this series I looked at golf’s past, especially how the PGA Tour in the United States became the pinnacle of the pro game, and also at golf’s fraught present moment, where the PGA Tour finds itself in a battle for future survival against the upstart / start-up LIV Tour equivalent.

In this essay I will try to look into a crystal-ball for what might await in the future of pro golf.

And to gain some insights into what may be in store in the coming months and years, perhaps the best thing to do is to look closely at how other sports navigated such upheaval and disruption in the past.

Let’s dive into three different pro sports and consider how things have developed there over the past two decades, to see if we might learn something more about golf’s current predicament and where it might go from here.

Cricket

In terms of administration, finances and spectator experience, no sport has seen as much upheaval in the past two decades as cricket.

Like golf, cricket originated in Britain and for a century or more it remained a fairly steadfast and standard experience for all who played it: from the amateurs on the village green, to the top performers selected to represent their county, to the elites who graduated to the national team.

Cricket coursed out of Britain to all ends of the old empire: Australia and New Zealand, India, South Africa and the West Indies in the Caribbean.

Test matches were nothing if not the slow pursuit of excellence. Matches were played over five days, and the batsmen did everything they could not to get out. Survival was the first port of call; the runs, when they came, were the cherry on top.

But television—the common factor in creating the demand that has led to all the money-driven disruption in sports these past few decades—unearthed something in cricket that the couch-dwellers among us noticed and loved.

Soon there were two choices: sit through the five slow days, or tune in that evening for the highlights. The purists and aristocrats, some with nothing more important to do on a Thursday afternoon, could stick to their traditional preference, but a growing audience of workmen and women could see the best bits and admire a fast bowler’s best spell or a booming six smashed over long-off.

The game would slowly and inexorably move in two directions at once, between the old ethos and the new entertainment value.

The old purists could still point to Test batting averages as the clearest indicator of ability. The new fans did not care a whit about that. They cared about seeing batters batting not blocking, or fast bowlers sending the middle stump spinning out of the ground.

The inevitable development was the formation of something revolutionary: the basic rules of how to score runs and how to get out would stay in place, but on top of them an entirely different game was built.

Whereas Test match cricket takes up to five days and as many “overs” (sets of six balls delivered by a bowler) as it needed, Twenty20 cricket is played over 20 overs each (120 balls) and starts and finishes in three hours.

The first Twenty20 international was played in 2005, and the Indian Premier League started three years later.

There are parallels and contrasts here with LIV.

The parallel is that the Indian Premier League is a new league in a shorter format, big on razzmatazz and noise. (One of the LIV slogans is “Gold But Louder”; for anyone who has witnessed an IPL match, its emblem might easily have been “Cricket But Louder”.)

There are big hits on the field, and the IPL is a big hit off it. Just this summer a new television rights deal will bring in $6 billion (Disney-owned Star India have forked out about $3 billion for their share), and the IPL chief, former India Test cricketer Sourav Ganguly, was quick to point out that the league’s per-game TV rights value is now second globally only to the NFL, placing it ahead of the English Premier League, the NBA and Major League Baseball.

It must be noted that if the IPL is a model that LIV would like to pursue (noise, innovative formats, a shorter league schedule, newfangled teams), there are both similarities and differences to note.

For one thing, perhaps the primary comparison between Twenty20 cricket and LIV Golf is not the IPL but its predecessor, the Indian Cricket League (ICL).

The ICL was the rebel equivalent, which started in 2007 but folded in 2009 after the formation of the IPL by the Board of Cricket Control of India (BCCI).

Several big-name players had signed up for the ICL, but as it was outside the system and not approved by all the governing bodies, and with threats of bans and de-registrations against players, the ICL never really stood a chance once the IPL arrived on the scene.

In this comparison, the future suggests that the PGA Tour, as the incumbent, would launch a similar shorter-form, high-entertainment competition to rival LIV; and there are many who would argue that the PGA Tour’s reaction to LIV, the establishment of a series of big-money, limited field, no cut events to take place in the autumn of 2023, is exactly that.

But LIV does have some advantages that were not available to the ICL:

It has already, in just two tournaments and a quickly growing rota of Top 50 players, gone further in 2022 than the ICL could manage in 2007,

Golf pros’ status as independent contractors makes it more difficult for the main Tours to prevent a rival from gaining ground once those contracts are in place, and

The Saudi Public Investment Fund has reserves of cash that the ICL backers could only have dreamt of

Cricket’s battles were played out in court, but in the end the landscape was changed forever.

The IPL is now an eight-week annual tournament, played in heaving stadiums, with many of the world’s most renowned stars on the field, and a massive global audience footing the bill through subscriptions and advertising exposure.

The stars come to India and cash in, but when their commitments there are done they return to their home countries and home teams for the rest of the year, and thus the uneasy peace between commercial entertainment and traditional prestige is maintained.

Whether we see something similar in golf—a resettling of the power base to the PGA Tour after a stern challenge, or a major shift away from US and their European / DP World partners to a more global and entertainment-focused competition backed by Saudi money—all of that is still to be decided.

What is almost certain is that golf and the way it’s played and watched at the top level will never be the same.

Boxing

As an individual sport administered by distinct governing bodies around the world, boxing is comparable to the current moment golf.

Yes, the competition structure is completely different, and the TV appeal of two big men slugging it out is invariably going to stir up the primal senses more than some gentlemen following a white ball around a field.

But there are a couple of relevant things to note from boxing’s recent decades:

1. The schisms that have ripped the sport’s administration apart at the seams

For more than four decades after 1921, boxing had one recognised world sanctioning body: the World Boxing Association (WBA), whose heavyweight belt was worn by the likes of Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano and Floyd Patterson.

The first split came in 1963 with the formation of the World Boxing Council (WBC), but take a look at the Wikipedia page of boxing organisations and you quickly drown in an alphabet soup.

The WBO (World Boxing Organization) and IBF (International Boxing Federation) arrived in the 1980s, and those four remain the recognised quartet of sanctioning bodies, but there are dozens of others all trying to claim their piece of the world boxing pie.

One key difference here is that, for all the money that washes through boxing, the brands of the sanctioning bodies are still indistinct.

Casual boxing fans may know exactly who Tyson Fury, Anthony Joshua, Deontay Wilder and the Klitschko brothers are, but could they identify the exact world titles they’ve held over the past ten years? Unlikely.

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf are different: more than they are governing bodies or tournament organisers, they are corporate brands in their own right. Corporate brands with billions of dollars behind them, and long lists of A-type executives with hands on the reins, are playing a power game more than anything else, and each will fight to gain or retain their share.

2. Those schisms make little tangible difference to sport’s appeal or commercial value

As far back as the Roman Empire, when the poet Juvenal immortalised the words “panem et circenses” (“bread and circuses”) those in charge knew that making sure the mob was fed and entertained would keep it satiated and docile.

From boxing’s backroom we can see some important things about human nature.

On the one hand, most casual fans—and let’s face it, for every rabid sports fanatic there are a hundred casual fans, and they are always the most profitable ones—have no real idea how the sport is run. What’s more, they care even less. This is just entertainment, after all. We still tune in, won over by the pay-per-view hype machine to crack out our credit card for the latest showdown.

On the other hand, the division between those who pay and those who profit is stark. You might not be able to tell an IBF belt from a WBA equivalent, but the power-brokers in those organizations are the ones who take money to the bank every time they sanction a big fight.

3. The shift away from the USA has been stark

While it’s not easy to find a reliable list heavyweight world title fights—which have long been boxing’s pinnacle event—I’ve compiled a list of 178, from James J. Corbett’s defeat of John L. Sullivan in New Orleans in 1892 to this August’s scheduled rematch between Oleksandr Uyk and Anthony Joshua in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Of the 111 heavyweight title bouts until 2001, the US was the location for 90 of them (or 81%).

Since 2002, that number has dropped to less than 38% as Germany, the UK, Russia (at least before their 2022 war) and now Saudi Arabia became bigger power-brokers in the sport.

Of course, there are many factors in that—it could be argued that the golden era of American heavyweight boxing came to an end when Mike Tyson bit Evander Holyfield’s ear in 1997, and the past two decades have seen the rise to prominence of Joshua, Tyson Fury (both British), Usyk and the Klitschko brothers (all Ukrainian)—so it would be foolhardy to point to things like venue alone and declare that America’s place on the world stage has faltered.

But it is a factor.

Between February 2008 and May 2014 there were 34 world heavyweight title fights; just one of them took place on American soil.

Vegas and New Jersey are now rivalled by Wembley, Hamburg and Jeddah.

UFC

Sticking with combat sports, it’s worth taking a quick look at the UFC, as there’s an argument to be made that it is this organisation more than any other that is the role model for what LIV Golf might become.

For one thing, the UFC is now 100% owned by Endeavor, the publicly-traded Hollywood entertainment company whose brands includes the sports management agency formerly known as WME IMG. (Clients of WME IMG have included several LIV players (notably Patrick Reed, Martin Kaymer, Lee Westwood and Ian Poulter.)

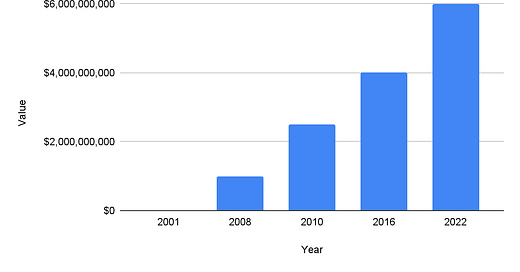

For another, the value of the UFC has exploded in 20 years, leveraging television rights negotiations and carefully engineering direct-to-consumer social media content to go from a broke circus sideshow in 2001, when it was sold to the Fertitta brothers for just $2 million, to become one of the world’s leading sports competitions: it was sold for $4 billion in 2016 and believed to be worth significantly more than that six years on.

Even more so than with boxing, the appeal of UFC is in its visceral can’t-look-but-can’t-stop-looking violence.

Golf is a different beast entirely, but as outlined in Part 1, the LIV team includes Chief Media Officer Will Staeger, who was a senior executive in seven years with Endeavor / WME IMG.

And with innovations at LIV already included team competition and a social media content arm that can be expected to attract significant further investment, it’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that it can chart a similar path and create new fans and new customers.

The UFC is watched now by millions of people worldwide, most of whom knew precious little about mixed martial arts 20 years ago. Can LIV create new golf fans out of people all over the globe desperate for their fix of more distraction, more entertainment, more rivalry, more content?

That seems to be what they’re aiming at.

What happens in golf?

From what we’ve seen in boxing, in mixed martial arts and cricket, there are very real potential upsides for golf.

1. There is no tangible limit on the entertainment value that might be created

TV rights valuations keep going in one direction: up, steeply.

From the single-channel experience of the mid-20th century to the on-demand streaming of today, developments in what we might broadly call “television technology” have been astonishing.

And from our habits, it is easy to come to a straightforward conclusion: this is what people want.

We want to watch live sport from the comfort of our own homes. The coronavirus pandemic placed that on pause for a few months until the suits could figure out how to move forward, but long before fans were allowed back in venues pro sports were taking place for TV audiences desperate for their fix.

The theory—seen in cricket, boxing, MMA and elsewhere—is that when you go all in on creating entertainment value, the masses will follow with their wallets open, and if that’s at the expense of accepted and traditional old values, then so be it.

Off the course, golf is already going through this journey from dusty elites to entertainment package.

Topgolf, the driving range company, has created a winning mix of range hitting and evening entertainment that has quickly seen it boom into a shining light of the American business landscape.

Its revenues passed the $1 billion mark in 2019 and the following year, amid the pandemic gloom, it was acquired by golf equipment company Callaway for $2.6 billion. Topgolf, whose assets include the game-changing Toptracer technology used by TV coverage at hundreds of global golf tournaments to show the arc of a golf shot after impact, has since been given a valuation forecast of more than $4 billion by 2025.

With all this growth in business value off the course, is it realistic to expect that someone will not come along to tap into that value on the course too?

This, and so much else, is in the melting pot for LIV.

Detached from the standard method of running golf competition, it can literally try whatever it wants.

For now that is shotgun starts, 54 holes and team play, but as CEO Greg Norman and his spokespersons have been pointing out whenever they get the chance, “we are just getting started”. If they can keep gaining momentum, the sky is the limit.

2. The first wave of LIV stars are heavy on the entertainment value

The supposedly simmering feud between Bryson DeChambeau and Brooks Koepka, which was supposedly placed on ice in time for them to be teammates on the US Ryder Cup team last year, is something that would be perfect for LIV.

For all their skills on the golf course, and the five Majors they’ve won between them over the past five years, the entertainment possibilities of a Bryson-versus-Brooks rivalry deepening on LIV made signing them a priority, and in relative terms, considering the money that sloshes around in the wake of international sport, could make the $250 million the Saudis reputedly paid to get them on board money well spent.

At the end of the day, what do most people really care about?

The pure artistry of a chokehold in wrestling? Or a bad-boy reputation to get behind or rail against?

Nate Diaz might not be in the top 100 mixed martial artists in the world. Every MMA fan wants to see him fight.

Something similar might happen for Brooks and Bryson and Phil Mickelson: they may not have, and might never have again, the combination of form, fitness and finesse that’s available to Scottie Scheffler and Rory McIlroy and Justin Thomas right now.

But they have an X-Factor that makes people turn on or tune in: whether they win or fall flat on their faces, the only thing that really matters is that people watch them do it.

3. The value of the Majors will only increase

For the vast majority of golf’s history, the Majors were all that most viewers really cared about.

The European or PGA Tours were the daily bread, but the Majors were the dazzling birthday cake, and we were lucky enough to have four birthdays every year.

That won’t change, and will likely only increase.

After all, the PGA Tour might have some influence on the Majors but has no direct governance on how they’re run.

The USGA (US Open), the Augusta National Golf Club (Masters), the PGA of America (PGA Championship) and the Royal & Ancient (the Open) will still organise their tournaments every year, backed by the weight of history and prestige.

For a decade or two the Players Championship, the jewel in the PGA Tour’s calendar, was suggested as an unofficial fifth Major, but with so many PGA Tour players now signing on with the upstart, that is almost certain now never to be the case.

Therefore the status of the Majors, as the only tournaments every year where all the best players in the world will show up, will be safe.

Unless they decide to ban players who join the LIV Tour—and that would probably be an irrational and self-defeating move on their part—their appeal and value will only increase.

That’s it for Part 5

In Part 6, the final chapter of this essay series, I will try to bring this full circle, asking—and trying to answer—some fundamental questions about golf: why we fork out our hard-earned dollars and euros to watch it, why we spend long hours attending tournaments, and why we pick up a club and play it in the first place.