Golf’s New World Order, Part 4: The Century of the Self

Part 4 of this six-part essay series on developments in pro golf in 2022.

In Part 1 of this essay series, I went through the history of the PGA Tour’s business model, the troubled present, and what the new business of the LIV Tour might look like. Part 2 considered the geopolitical moment, in particular the possible decline of the United States as the dominant global superpower and the aspirations of Saudi Arabia to use its oil riches to rise the international political ladder. Part 3 was all about the practice of sportswashing, which the Saudis’ strategic investments are are often accused of.

In Part 4, I will consider the simple question:

Why might it be that so many players in the top 0.5% of their profession choose to risk a highly lucrative career by accepting cash from a new league backed by men for whom human rights convetions does not appear to be a key priority?

There’s no obvious one-size-fits-all answer. There are, for example, starkly different driving forces behind Pat Perez, a journeyman 46-year-old, and Bryson DeChambeau, who is just 28 and should still have the most producive years of his career ahead of him.

The Perez factor—and that of other players like Sergio Garcia, Graeme McDowell and Louis Oosthuizen, aged 42, 42 and 39 respectively, all with memories of one Major win that slip further and further into the past every week they’re not in contention—is perhaps understandable.

Their best form behind them, several years to wait for the late-career bump of the Champions Tour, and (one might reasonably assume) coaching teams, lifestyles, egos and wives that have become too accustomed to life in the fast lane, it is in many ways understandable that their attention would be grabbed by the promise of a guaranteed cash injection from elsewhere.

After all, for all their career earnings, they are still human, and it is basic human nature to feel aggrieved when you feel you’ve something important.

Take McDowell, for example.

He had four $2m+ seasons between 2012 and 2016. Since then he has passed the $1m mark just once, and his last three years’ earnings read $751,000, $212,000 and $170,000. For many people they might be the highest-earning years of a career, but might McDowell have had some dark nights of the soul as he contemplated his faltering abilities and waning earnings?

The example of Perez is even more pertinent.

In the winter of 2016/17, Perez went on a rare career heater, with four Top 10s in five tournaments and a win at the Mayakoba Classic in Mexico. Those results propelled him to earnings of more than $4 million that year, but it’s worth looking back at the season just before that: 11 tournaments, eight missed cuts, a best finish of T41 and a grand total of earnings for the year of $47,840.

The PGA Tour being what it is, with no guaranteed prize money—a missed cut means no income that week—the season can amount to a real grind to keep your card for a few dozen players each year.

We might look at those players from afar, from our home office or corporate cubicle or truck cabin, and feel envy at their living and their lifestyle, but without asking anyone to feel sorry for the multi-millionaire, can we truly imagine the thoughts of Pat Perez at Christmas 2016, when he was just 40 years old and his form—and income—had completely deserted him?

Before and after his first tournament at LIV, when he won approximately $900,000 despite an eight-over-par 80 in his final round (he won $750,000 for being part of the winning Four Aces team), Perez looked and sounded like someone who was surfing a surprise and beautiful wave. (He said it was like “winning the lottery”.)

We might criticise his motives, his ethics, his cold acceptance of money that many people say is dirty or bloody or both or his demeanour in the pre-LIV press conference. But if we give ourselves a moment, even if some among us might disagree with his actions, surely we can also understand why he took them.

So no, this piece is not about why people like Perez, McDowell, Garcia or Oosthuizen—or Martin Kaymer or Paul Casey or Lee Westwood, other players with their best long behind them—might take the money.

This piece, instead, is about those who already had so much and the promise of so much more, and still put their future at risk for an unknown quantity where the cheques are signed by men who write in an alphabet we don’t understand and might well be evil despots.

For players like DeChambeau, Brooks Koepka, Dustin Johnson, Patrick Reed and for Phil Mickelson too, the clear second best player in the era of perhaps the greatest of them all, how do we understand their motives and actions?

Is it just a simple case of greed, or is something bigger, something deeper, at work?

The rest of this essay will try to hazard a guess.

The format plus the payday

The second section below have little to do with golf, specifically, so let’s start with something that does.

A lot of criticism has rained down on the LIV players’ heads whenever they’ve spoken about their excitement in taking part in a “new and innovative” golf format: a shotgun start that means everyone tees off at the same time and the day is done for all players inside four or five hours; three days and no cut, which is alluringly both more than they’re guaranteed on the PGA Tour, and less than they might have to play there; and team play, where irrespective of how good or bad things might be going at an individual level, every stroke might still matter until the final putt drops.

What is unsaid in this is, the criticism goes, what’s most important. That the apparent appeal of the format (or the occasional suggestion that “growing the game” around the world could satisfy some unfulfilled and selfless desire to give back) is the Trojan Horse the players are offering to the public when their real motivation is what’s inside: those boatloads of guaranteed cash.

But it could well be that there is a lot of truth to the appeal of the format, once we keep an open mind and add a dollop of nuance.

Is it unreasonable to suggest that two things might be true: that the innovative formats might be appealing, AND that the players might also doubt their ability to continue to compete on the PGA Tour, whether that doubt comes from age or form or physical problems or a gnawing mental fragility?

There will be more about cricket’s short-form Twenty20 innovation in Part 5 to follow, but let’s look for a moment at the series of matches taking place this month between two of the top sides in international cricket, England and India.

Cricket is an 11-a-side game. Test matches have long been regarded as the pinnacle of the game: they take place over five long days, both teams typically wear traditional white uniforms, and dogged defence and survival plus occasional attack is usually the winning strategy. T20, on the other hand, is done in three hours, the teams wear uniforms in their national colours, players aim to move fast and entertain, and the crowd often get involved with a loud atmosphere in the beer-soaked stands.

England and India played a Test match last week, and T20 games this week. High-class international cricketers took part in both games, but no player played both. England and India—and all other international cricket teams—have specialist Test cricketers and specialist T20ers. It’s generally accepted that players excel in one or other format, rarely both. Often, top-class cricketers drop off the Test scene and refocus on the T20 games for the end of their career.

Is it too much of a stretch to see certain parallels with golf here?

The Saudi money, and the unwillingness of the players to speak too much publicly about the part that has played, are clearly key factors that are not acknowledged enough, but the ridicule aimed at players who find golf’s new formats appealing might still be a little wide of the mark.

A century of psychology and the maximised self

Okay, the golf rationale now dealt with, let’s now consider some other possible reasons that players might have chosen to take these big decisions with their lives and careers.

I mentioned Sigmund Freud and Edward Bernays in passing in an earlier essay in this series, and let’s return to psychology and make a whistle-stop tour of the developments that have taken place in our understanding of the psyche over the past century, and see how they might apply to what’s going on in pro golf in the summer of 2022.

The first philosopher, and the most recent, is a fictional one: Bobby Axelrod, the central character of the hit HBO show Billions. In one scene the billionaire moving-and-shaking hedge-fund boss talks with his protégé, Taylor, who has been grappling with a fork in the road in their own rapidly rising career, thinking over whether to be loyal to the fund, or chart their own path.

Axe tells Taylor a story about how he got to the top, finishing with a polished pearl of wisdom about the maximised self:

“The moral of the story is, you get one life, so do it all.”

The maximised self is perhaps the end result of a century of focus on the self.

Freud’s central theory was that a wild sex drive and raw and violent emotions were the hidden motivations that governed human nature and behaviour, a relic of our animal past, and must be overcome if we are to live and work together in a peaceful and civil society.

His one-time colleague Wilhelm Reich decided on the same thing but took a different direction: that human beings were ruled by an ungovernable sex drive, but that it must be allowed to be expressed, and that the repression of it was the cause of all man’s problems.

Carl Jung explored the self deeply too, and offered another theory: that all humans were bound together to the rest of humanity through a collective consciousness, and that all of us contained four elements, the persona, which concealed our true inner being and which we presented to the world; the animus or anima, the presence of the opposite sex within us, as part of that collective consciousness; the shadow, a wild inner force that is neither explicitly positive or negative, and that brings about our most creative and most destructive energies; and the self, the true and unified being, which it is our whole life’s work to fully discover and inhabit.

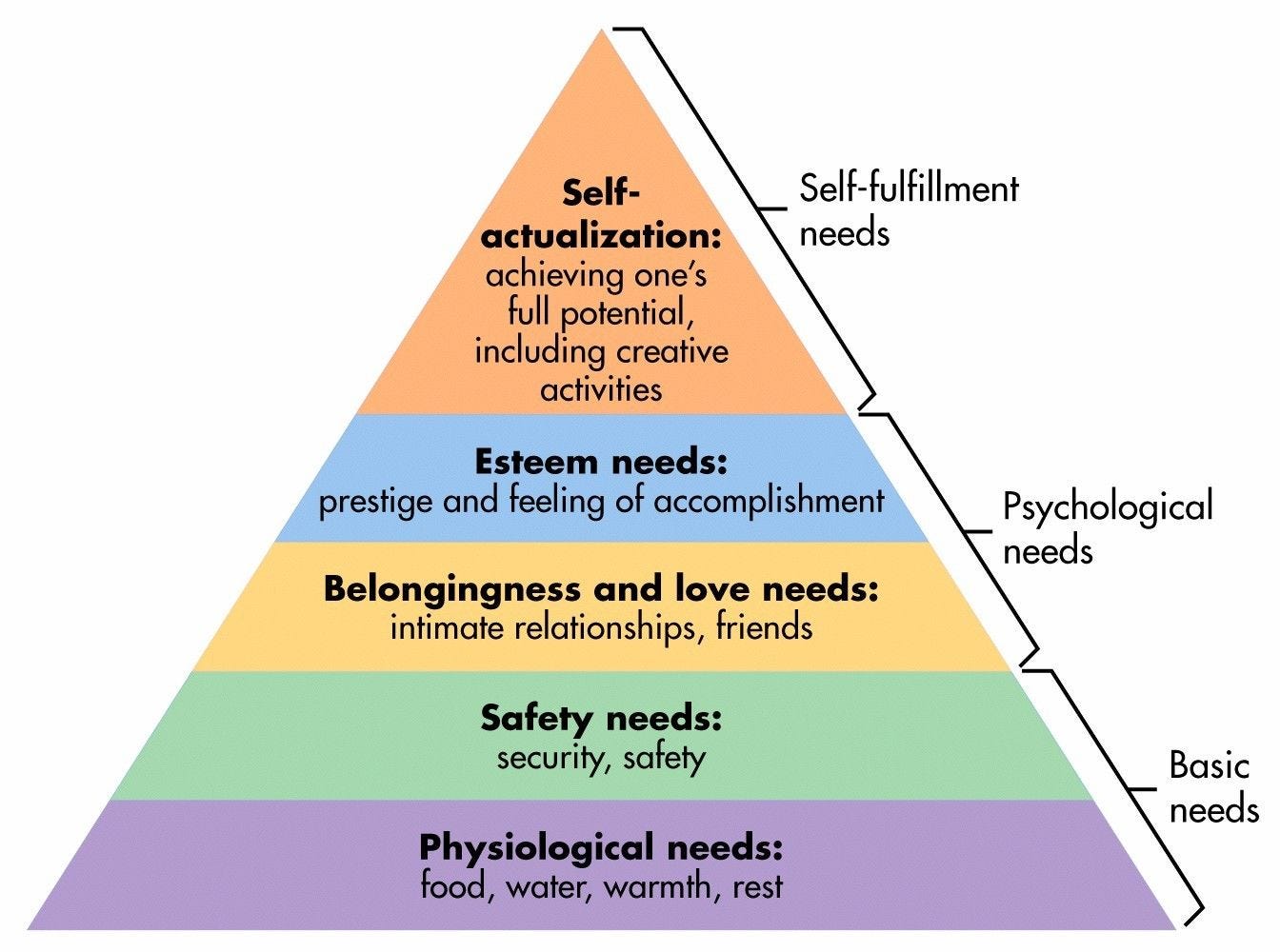

Abraham Maslow’s offering to the science of psychological understanding was the hierarchy of needs, a ladder of requirements that all human beings go through. It starts with basic physiological needs, including food, water and warmth; moves through safety (security and shelter); love (friendship and intimate relationships) and esteem (prestige and the feeling of accomplishment). At the top of Maslow’s pyramid, the ultimate endpoint of every full and fully fulfilled human life, is self-actualization: achieving one’s full potential, the pressing and almost unbreakable desire to become the most that one can be.

Carl Rogers also spent key chunks of his working life looking at the self, especially in person-centred therapy. His primary ideas, echoing Maslow’s self-actualization, were that all people possess an inherent need to achieve their potential; that people tended to have a concept of an “ideal self” which they were invisibly drawn to achieve; and that unconditional positive regard was a key element of both care and self-care: that whether one’s thoughts and feelings were outwardly good or bad, they should be treated positively and without negative judgment.

Over the course of about sixty years, these five men—Freud, Reich, Jung, Maslow and Rogers—cultivated an extraordinary shift in the way we see ourselves. We can only assume that for previous generations the self was hardly worth talking about. Such inner desires were present, obviously, but they were rarely allowed to the surface, and whenever they did the only guarantee was that scandal would ensue.

The psychologists, and the army of professional psychiatrists and self-help gurus they inspired, led to an endless and deep obsession with the self.

In August 1976, the great narrative journalist and later novelist Tom Wolfe wrote a searing essay for New York magazine titled “The ‘Me’ Decade and the Third Great Awakening”. Almost half a century on, the piece is still well worth reading. Its first line, under the section heading “Me and My Hemorrhoids”, could have been lifted straight from the psychologists:

“The trainer said, ‘Take your finger off the repress button’. Everybody was supposed to let go, let all the vile stuff come up and gush out.”

I will copy-paste one early paragraph here, in the hope that it gives you some of the pleasure it gave me:

Many others are stretched out on the carpet all around her; some 249 other souls, in fact. They’re all strewn across the floor of the banquet hall with their eyes closed, just as she is. But Christ, the others are concentrating on things that sound serious and deep when you talk about them. And how they had talked about them! They had all marched right up to the microphone and “shared,” as the trainer called it. What did they want to eliminate from their lives? Why, they took their fingers right off the old repress button and told the whole room. My husband! my wife! my homosexuality! my inability to communicate, my self-hatred, self-destructiveness, craven fears, puling weaknesses, primordial horrors, premature ejaculation, impotence, frigidity, rigidity, subservience, laziness, alcoholism, major vices, minor vices, grim habits, twisted psyches, tortured souls—and then it had been her turn, and she had said, “Hemorrhoids.”

This psychology, this incessant, endless and torturing exploration of our being, was to the 20th century what Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama were to the 15th.

This was exploration. This was the search for true self! for absolute expression! for self-actualization!

And this became the essence of the maximised life, and half a century of being exposed to it, of being encouraged to embody it, of being made aware, in the mass media and the bathroom mirror, of all the ways we were falling short of it, has brought us to where we are today.

And it’s a weird and convoluted place, 2022.

Because on the one side the maximised life is an aspirational and worthy pursuit. Its appeal is the reason why the last two lines of Mary Oliver’s poem “The Summer Day” so often appear on Internet graphics and mugs and mousepads—

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?

—even though the maximised life is probably the polar opposite of what the rest of the poem was actually saying to us.

The maximised life is the reason we find such inspiration in Marianne Williamson’s words about life:

“Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, 'Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous?' Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won't feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. It's not just in some of us; it's in everyone. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others.”

The maximised life is seen when people do ten Ironman triathlons in ten days. It’s seen in the appeal of David Goggins’s unique brand of self-empowering self-punishment. It’s seen in the way Jordan Peterson gathers millions and millions of followers at the same time as he is ridiculed in mainstream media, his messages, like “stand up straight with your shoulders back” and “imagine who you could be and then aim single-mindedly at that” appealing to a generation of displaced men (and plenty of women too). It’s seen, too, in Hemingway’s praise for the matador: “Nobody ever lives their life all the way up except bull-fighters.”

Even if they differed on the specifics, almost all the most influential psychologists of the past century seemed to agree on one thing: that the self, the inner being, contains desires and energies that we might never be able to explain, intent on creating something big and bold with the one wild and precious life we’ve got.

Bobby Axelrod’s “do it all” might be the unspoken maxim for a generation, especially a generation of mostly American mostly men.

In this maxim, ideas of one’s place in history, of the long continuum of the past to the future, of prestige and legacy and tradition, all those ideas are subservient to the quest of becoming fully self-actualized.

The trouble with the quest for self-actualization is that from the outside it often looks like greed.

Maybe two Majors and a couple of hundred million dollars is enough out of old-school golf for Dustin Johnson, and he and his new wife can now explore the fullness of what the rest of their lives might contain.

Maybe Brooks Koepka’s combative spirit was driven by the desire to take on a few enemies off the golf course in the same way as he tries to take them on inside the ropes, and that he and his new wife are energised by that us-against-the-world narrative too.

Maybe Bryson DeChambeau is intent on leveraging his brand name recognition, and that he’s happy to leave a quest for golf greatness behind him—if, indeed, that was ever part of the plan—and focus instead on the business of building major businesses and charitable foundations out of the fertile YouTube content ground of ball-speed-science, long-drive and party-golf enthusiasts. And maybe LIV’s millions is the best vehicle to help him make that happen.

Maybe Patrick Reed had enough of disliking everyone and everyone disliking him, and felt the Four Aces would satisfy the Maslowian human need for belonging.

Maybe Phil is still, somehow, somewhere on Maslow’s lower rungs and really does need the money.

Maybe Talor Gooch, who still wants to play in both places, was just badly advised.

Maybe the simple explanation is the right one: that money always has its own logic and momentum, and that cash is always king and money always talks.

Or maybe there’s a kernel of truth in what I’ve explored here, of a century of human psychology and how it’s changed so much about the way so many of us see ourselves and the world around us.

That’s it for Part 4

Part 5 will take a look around the sporting world and see if we might be able to predict golf’s future from the ghosts of other sports’ past.