Golf’s New World Order, Part 2: The Geopolitical Backdrop to LIV and the PGA Tour

In Part 1, I delved into the business of both the established PGA Tour and the upstart LIV Golf equivalent, to try to develop a better understanding of what exactly is going on in the world of pro golf right now.

In this essay, the second in a six-part series, the focus turns broader, trying to figure out what we might learn from the wider geopolitical, macroeconomic and technological developments of the 21st century so far, and the changes those developments are bringing about in the world, for Presidents and autocrats and for me and you too.

It looks closer, specifically, at the United States and Europe and Saudi Arabia, about their place in the world right now and the direction they may be headed.

And it looks also at the technological landscape in which all of us now live and participate, a landscape in which we are both players and being played, in which all of us are more informed, or more misled, than any generation in the history of humanity.

The Ever-Changing World, Before Our Eyes But Out of Our Sight

It’s been a mad couple of decades.

As the world reeled from the fall-out of the global financial crisis, through democratic upheaval epitomised most obviously by the anti-Establishment votes for Brexit and Donald Trump, and through a two-year global pandemic, a few things about how the world works have become clear.

These things relate to information, to human nature and to truth itself.

To get a better understanding of the world in which we live—and the world in which the PGA Tour and LIV will fight their battles, the world in which cultures are clashing from West to East and back again—I will try to go through each one in turn, before returning specifically to the USA and Saudi Arabia, and what might happen next.

1. How information is a firehose

Facebook launched on a college network in 2004.

The first YouTube video was uploaded in 2005.

Twitter came along in 2006.

In 2007 Steve Jobs stood on a stage with the first iPhone in his hand.

And in 2008 Lehman Brothers collapsed and a year of financial contagion spread throughout the old Euro-American “west”, from the US to the UK, from Iceland to Greece through Ireland, Italy and Spain.

All of us live in Pompeii, and these five developments were the eruptions of Vesuvius.

In what felt like a blink of an eye, it became apparent that everything about the way everything was done was in the process of being destroyed.

Like volcanic matter on the Bay of Naples, the destruction carried all the nutrients for lavish regrowth above what’s buried. In place of the old ways, new and fresh ways of living, working and being came to the fore every day.

Information—the very building blocks of society and culture—could never hope to escape the destruction-creation cycle.

For a century and a half, after the explosion of mass-market newspapers of the mid-19th century through the rapid growth of radio and television over the next 100 years, information had appointed gatekeepers, the controllers who mediated what could and could not be brought into the open.

If there was ever an agreed consensus on what made “the news”, the consensus began to fray and collapse as the influence of the Internet took hold.

Suddenly, starting with the “weblogs” of early adopters of the mid-1990s, and then exploding with the onset of social media in the global recession sparked by the financial crisis of 2007-8, almost everyone in the world had a soapbox to stand on, a loudspeaker in their hand and the world at their feet.

The task of mediating this information explosion is, literally, impossible.

The information that you and I and everyone else read and produce every day—a billion times a minute, every minute, every day—has created a nonstop firehose and all the old gatekeepers are drowning in the flood.

How much has the information landscape changed?

How many more years will it take for us to truly appreciate the upheaval all of us have experienced in less than two decades?

What are its effects on us, on our relationship with the world around us?

The answers to these questions and more could help explain our view of the world, what adds up to our individual and collective realities, and how information—what we create, what we share, what we believe—changes everything about our world, right down to the way our societies and states work.

But we are still some way away from knowing what those answers are.

2. How human beings are mouldable

As we consider the fallout of this information explosion, it’s worth looking back at the work a century ago of Edward Bernays, the so-called “father of public relations”.

Bernays was the nephew of the Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, and he became intensely interested in the work of his old uncle.

His interest, though, lay not in its application for the wellbeing of individuals, but in how Freud’s research might influence those individuals en masse.

In his 1923 book Crystallizing Public Opinion, Bernays wrote:

Public opinion is the aggregate result of individual opinions—now uniform, now conflicting—of the men and women who make up society or any group of society. In order to understand public opinion, one must go back to the individual who makes up the group.

The mental equipment of the average individual consists of a mass of judgments on most of the subjects which touch his daily physical or mental life. These judgments are the tools of his daily being and yet they are his judgments, not on a basis of research and logical deduction, but for the most part dogmatic expressions accepted on the authority of his parents, his teachers, his church, and of his social, his economic and other leaders.

…

The cardinal quality of the herd is homogeneity. The biological significance of homogeneity lies in its survival value. The wolf pack is many times as strong as the combined strength of each of its individual members. These results of homogeneity have created the "herd" point of view. One of the psychological results of homogeneity is the fact that physical loneliness is a real terror to the gregarious animal, and that association with the herd causes a feeling of security. In man this fear of loneliness creates a desire for identification with the herd in matters of opinion.

…

We may sincerely think that we vote the Republican ticket because we have thought out the issues of the political campaign and reached our decision in the cold-blooded exercise of judgment. The fact remains that it is just as likely that we voted the Republican ticket because we did so the year before or because the Republican platform contains a declaration of principle, no matter how vague, which awakens profound emotional response in us, or because our neighbor whom we do not like happens to be a Democrat.

Even now, just about 100 years after Bernays wrote the words, their resonance escapes most of us most of the time, but that does not mean they don’t hold deep truths about the way our world works.

We are part of a herd, and our behaviours are mostly governed by emotional responses we are scarcely aware of. If somebody finds a way of influencing—or even controlling—the herd, then the collective emotional response will dictate the behaviour of a vast number of individuals within it.

Humanity’s greatest breakthroughs during the rest of the 21st century and beyond may relate to outer space (cosmic engineering, quantum physics and interplanetary travel) and inner space (psychology, neuroscience, motivation and behaviour).

We know precious little yet about either, each new discovery only shining a light on all we don’t yet know.

What we can be fairly sure of right now, even as we’re still unable to do anything about it, is that our behaviours are often not in our own best interests.

We are influenced, maybe even controlled, by unseen powers exploiting our emotional needs for profit. (And it may be that in the corporate capitalist machine there are hundreds of millions of people all being similarly exploited by the forces they’ve helped to build.)

Often, we see that we’re steering towards the cliff face, but we’re unable to change course. We are pre-diabetic, but can’t keep our hands out of the candy jar. We know that our best work today could make a positive difference but instead we curl up for Season 8, Episode 6 of whatever is distracting us right now.

3. How the truth is difficult to pin down

In what we might call the “Western world”, the development of judicial systems over 300 years created in democratic institutions the final arbiter of the truth.

The centuries-old system of legal precedent, combined with agreements about morality—a deep-seated sense of right-and-wrong-ness—that owed much of its provenance to the influence of two millennia of Christian ideology across the English-speaking world, established a sometimes-grudging but ever-present respect for tradition and authority throughout the dominant cultures and societies, first the British empire in the 19th century and the American empire that succeeded it in the 20th.

These truths were handed down, father to son, through the generations. The slogan of the establishment, and all those who wanted to join the establishment, could have been simply: This is how we do things here.

The rapid growth of the Internet, and its polarised and polarising extremes of truth and untruth, crashed head-on with the global financial crisis of 2007-09: suddenly, the curtain was pulled back and everyone saw that the great and powerful Oz was just a lot of little men pulling a lot of levers.

The world of high finance—the backdrop of the PGA Tour and LIV Golf standoff, and the backdrop of the US and Saudi Arabia and all other participants in a world which stretches invisibly through the ether from New York to Beijing, Tokyo to Dubai, London to Hong Kong—succeeded in creating a complex million-headed money hydra. Debt is on the liability side of the balance sheet for you and me but it is the ultimate asset traded by all the financial institutions, and debt was packaged and sold, and repackaged and resold, again and again and again until the people buying and selling the debt packages had no damn idea what exactly was in them.

This was the story of The Big Short, the Michael Lewis book and subsequent hit movie which recounted what had happened on finance house trading terminals to bring down banks from Wall Street to Athens.

As clear-thinking ordinary people all over the world began to take a closer look at the way finance worked, two things became clear on either side of the old Euro-American worldview.

Europe

On the one hand, in Europe, Government austerity measures were imposed on people in several countries, including Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain—the so-called PIIGS of Europe—leaving those countries on their knees economically and negatively affecting the entire continent.

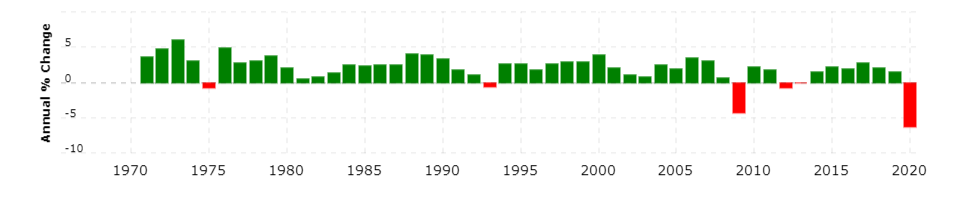

Between 2009 and 2020, four years showed negative GDP—2009, 2012, 2013 and 2020—and the highest GDP growth in all the other years was 2.8%, in 2017. (For comparison, from 1966 to 2008 there were just two years of EU negative GDP growth: 1975 and 1993.)

Data: World Bank / MacroTrends

GDP growth can be a crude measure. How about the happiness of the people? A look at antidepressant usage might tells us something.

An analysis by OECD in 2019—the OECD is an inter-governmental organisation for economic co-operation and development, whose members account for more than half the world’s GDP—found that the average use of antidepressants among adults across the 29 surveyed countries was 63 per 1000 people per day—in real terms amounting to approximately 60 million people taking antidepressants EVERY DAY, a number that more than doubled since 2000.

There are many factors at play here, including (possibly) increased drug effectiveness, more widespread availability and the success of pharma companies in marketing their treatments.

But in general and simple terms, tens of millions of happy and healthy people are not given antidepressants to take every day.

The USA

Drugs also play a stark role in the United States—the number of drug overdose deaths increased by 400% from 1999 to 2019, mostly as a result of the opioid crisis.

Again, the reasons for that are deeply complex, but a few factors jump out.

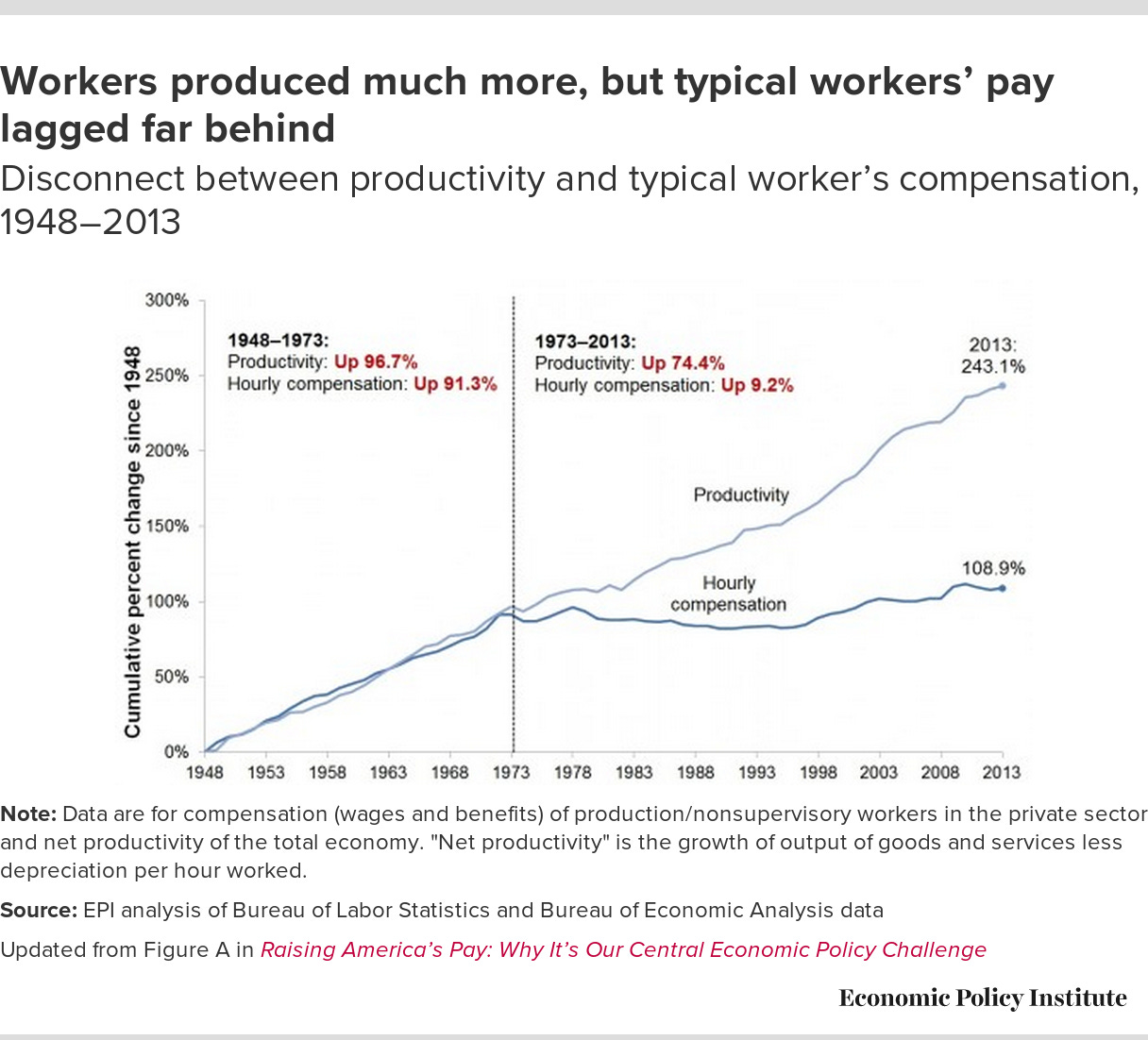

For one thing, the widening gap between the work people did and how much they were paid was becoming apparent.

The gap between productivity and pay had been growing since 1973. (Graph below from the Economic Policy Institute.) In simple terms, wage growth for ordinary workers completely stagnated, leaving entire generations of people much less prosperous than their forefathers, and widespread inequality and unfairness appearing to be everywhere they looked.

Probably related, many scholars identified a “meaning crisis” sweeping North America.

John Vervaeke, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, has spoken at length about the crisis—he has a 50-part lecture series titled “Awakening from the Meaning Crisis” on YouTube.

David Graeber, the late anthropologist, published Bullshit Jobs in 2018, describing such jobs as

a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence

and argued that more than half of all jobs—from admin assistants to door attendants, middle management to corporate compliance officers, lobbyists to telemarketers—were completely pointless.

While there are more and more religions, sports and clubs, participation in them is falling.

In short, we increasingly work completely meaningless jobs and come home (or step out of our home office) and find more meaninglessness waiting for us there too.

Stripped of meaning in our lives in the real world, we allow ourselves to get pulled deeper and deeper into the virtual world, where we find evidence for every mad idea we’d like to be true.

As this tragic merry go round spins faster and faster, the essence of what is true, and the fabric of respect and positive ethics that keeps us moving forward as a society gets eroded.

We begin to see bullshit and corruption everywhere—both in what is already bullshit and corrupted and in what we imagine to be—and our frustration turns to anger, and our anger to rage, and we look for somebody, anybody, to blame.

Right across the Western world, the growth in anti-Establishment perspectives has been increasingly evident, a shift noticeable most obviously in the pro-Brexit and pro-Trump votes of 2016, ballots that were much less for anything in particular than they were against everything about the way things were.

Covid-19 fast-tracked this trend.

Suddenly so much about the way things were seemed obviously broken or corrupt, yet one of the things most apparent was that almost everyone was reluctant to say so.

As leaders all over the world rallied to make decisions in the face of a global and invisible health threat, as scientists rushed to consensus and sought to silence the old colleagues who asked inconvenient questions, as massive pharma corporations tried to influence or control the narrative through political backrubbing and media ad spend, the old Hans Christian Andersen fable came readily to mind:

“I'd like to know how those weavers are getting on with the cloth," the Emperor thought, but he felt slightly uncomfortable when he remembered that those who were unfit for their position would not be able to see the fabric. It couldn't have been that he doubted himself, yet he thought he'd rather send someone else to see how things were going. The whole town knew about the cloth's peculiar power, and all were impatient to find out how stupid their neighbors were.

“I'll send my honest old minister to the weavers," the Emperor decided. "He'll be the best one to tell me how the material looks, for he's a sensible man and no one does his duty better."

So the honest old minister went to the room where the two swindlers sat working away at their empty looms. "Heaven help me," he thought as his eyes flew wide open, "I can't see anything at all". But he did not say so. Both the swindlers begged him to be so kind as to come near to approve the excellent pattern, the beautiful colors. They pointed to the empty looms, and the poor old minister stared as hard as he dared. He couldn't see anything, because there was nothing to see.

"Heaven have mercy," he thought. "Can it be that I'm a fool? I'd have never guessed it, and not a soul must know. Am I unfit to be the minister? It would never do to let on that I can't see the cloth.”

The truth is never straightforward, especially when we cannot agree on basic things, and when we refuse to see the things before our eyes.

America, Saudi Arabia and the future of the world

It is in this landscape and against this backdrop that geopolitics and macroeconomics plays out: the future of the world, as influenced by the active whims of a tiny number of people and the passive apathy of the rest of us.

In the destruction-creation cycled facilitated by the Internet and fast-tracked by the global financial crisis, the rise of ungovernable tech platforms and the Covid-19 crisis, we are only beginning to appreciate what is being destroyed and what is appearing in its wake.

And one thing that the overwhelming majority of us—busy with our daily lives and preoccupations and little joys and tragedies—are as yet unaware is how Western society, as we and several generations before us have come to know it and expect it, is being eroded steadily day by day by day.

Western society and culture held that America was the great and powerful guardian of the world.

It held that customs and mores established over a couple of centuries would last forever.

It held that English was the language of business and commerce and entertainment, and that anything not-English, and certainly anything where we can’t even decipher the alphabet—Russia, China, Arabia—is not just different, but worse. Weaker. (The third world became the developing world, and some parts of that were tagged as “emerging”, but only in the context of index funds created and packaged and sold at a profit.)

America gave us Hollywood, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, Louis Armstrong and Nina Simone, Tom Cruise, George Clooney and Brad Pitt, Tom Brady and Tiger and Michael Jordan. The Beatles and Bowie and the Rolling Stones were English but it was against the mirror of America that they became something bigger, bolder, better. America had Prohibition and bootlegging, it had the Bible Belt and Sin City, it had the snows of Aspen and the sun of Florida and the surf of SoCal.

America had everything you could ever want, from sea to shining sea. It could be forgiven for seeing itself as the kingpin of the world. After all, that’s what it showed itself to be in the two World Wars, and if things didn’t go according to plan in Vietnam or Iraq or Afghanistan, it still mostly held the surety of its convictions.

When you hold the whole world within your borders, you might be forgiven for not seeing the bigger picture.

But the bigger picture is rising into view, and it might not be a pretty one for America.

Amid the chaotic military withdrawal from Afghanistan, Russia’s assault on democratic values in Ukraine and the unexpectedly rapid growth of Asia’s taste for success (in China and Korea and the Middle East), amid all the culture wars and the public shamings and the ridiculous tribalist polarisation of everything, America’s place in the world is under threat.

The last bulwark against its demise may well be the dollar: being the world’s reserve currency is no small thing.

But that too may be in peril.

Reserve currency is a roundabout way of saying to a particular part of the world: “You’re number one”.

Whether it’s Venice in the 1500s or the US in the 2000s, the place with the most sustainable boom becomes the place everyone else wants to do business with, and the virtuous circle continues: more money pours in, which creates more productivity, more success and more wealth, which in turn attracts more money. When the dominant companies and industries come from one country it becomes inevitable that country will become the reserve currency.

But the slope when it starts to appear can be a slippery one. When economies begin to slide, debt mountains tend to spike and nobody wants to be the one left holding the bag, the collective psychology can turn to panic mode quickly enough, and the virtuous circle becomes a vicious cycle with its own unerring downward momentum.

Since 1450 there have been six major world reserve currencies: Portugal until 1530, Spain until 1640, Netherlands until 1720, France until 1815, Britain until 1920 and the US until now.

The span of a reserve currency is typically around a century. The US dollar passed that point in 2020.

So-called Modern Monetary Policy, or MMT, was held up as the saviour in 2020 when it facilitated a massive public spending spree to combat the worst effects of Covid-19 on businesses and individuals.

Time will tell whether that was a revolutionary break from dusty old economic theory or another nail in the coffin of the US as a global superpower.

What of Saudi Arabia in all this?

The Saudis’ state investment fund has, in the past two years alone, emerged as the backer of LIV Golf, the suitor that brought Formula 1 racing and boxing title fights to the desert, the owner of English Premier League club Newcastle United and investor of tens of billions of dollars in US stocks.

All these investments are not scattergun. They form part of a collective strategy, under the heading Vision 2030, which outlines ambitious plans to increase Saudi Arabia’s influence on the global stage, and establish it as a central focal point of European and Asian trade.

The Saudis’ economic strength has long been based on its oil reserves, and that will continue to be the case, but their investments right now are, per Vision 2030, across everything from human capability to financial sector development to health sector transformation. Every area of the Saudi state is getting a massive shot in the arm, with the aim of prospering far into the future in a post-oil world.

Whenever business with Saudi Arabia is mentioned, and this has been relentless during any discussions about LIV Golf, the Saudis’ record on human rights is typically brought out for examination.

And for anyone who has even had a taste of Western freedoms (and after all, Western freedoms are all four cornerstones of established human rights conventions) it makes for horrific reading.

Amnesty International has a page on its website detailing the many ways Saudi Arabia violates human rights:

Blogger Raif Badawi was sentenced to 10 years and 1000 lashes in 2015 having been deemed guilty of “insulting Islam” for founding a website for political debate.

Courts in Saudi Arabia continue to sentence people to be punished by torture for many offences, often following unfair trials.

Saudi Arabia is among the world’s top executioners, with dozens of people executed by the state every year, many in public beheadings.

All of Saudi Arabia’s prominent and independent human rights defenders have been imprisoned, threatened into silence, or fled the country.

Going to a public gathering, including a demonstration, is a criminal act, under an order issued by the Interior Ministry in 2011.

Women and girls remain subject to discrimination in law and practice, with laws that ensure they are subordinate citizens to men.

Security forces frequently use torture in detention, and that those responsible are never brought to justice.

The Saudi Arabian authorities continue to deny access to independent human rights organisations like Amnesty International, and they have been known to take punitive action, including through the courts, against activists and family members of victims.

The Human Freedom Index is a ranking of human freedoms around the world, measuring 82 distinct indicators of personal and economic freedom in areas such as the legal system, security and safety, movement, civil society, the legal system and freedom to trade.

Compiled by the Cato Institute and the Fraser Institute, its 2021 list was topped by Switzerland, New Zealand, Denmark, Estonia and Ireland. In the list of 165 countries, Saudi Arabia came 155th. On the “personal freedom” metric, only Somalia, Egypt, Yemen and Syria were rated worse. (A party-loving friend spent three years working in construction in Saudi. After he came home, he said: “It’s the worst place in the world.”)

Most of us see the world through the prism of something we take for granted: individual freedom. In Europe and the US we have the freedom to launch a startup and aim for a billion, the freedom to work hard or not, the freedom to shoot heroin into our veins until we die on a park bench.

These freedoms are worth something to all of us, worth everything to many.

As we see photos of dozens of migrants clinging to a raft in the Mediterranean Sea, or hear of another tragedy of dead Syrian stowaways in the back of a refrigerated truck, we realise that many people around the world unaccustomed to such freedom risk everything for the chance of experiencing it.

And yet despite all this, despite our misgivings about human rights, despite the empathy we might feel about the type of life someone the same age and sex as us might be living in Saudi Arabia at this moment, despite it all, Saudi Arabia remains a business partner and ally to so many.

Things might be different if we weren’t going through the biggest energy crisis in 40 years and the Saudis were not sitting on the world’s greatest supply of oil.

That being the case, we might hold them to account for their human rights record, or shun them at the very least.

But that’s not the case.

Instead, we’re hooked on black coke and the Saudis are the dealers with the best stuff.

Freedom or power

The princes and plutocrats and power-brokers of the new culture have something even more valuable than freedom: they have all the power and all the money.

The power comes from money, and the money comes from oil, and the oil comes from the ground beneath Arabia.

It might be another decade or another century before the wheel fully turns and we find ourselves, slowly or suddenly, occupying a new third world in the shadow of the dominant glow emanating from the Middle East and Asia.

Politics and geopolitics has its own strange momentum. Even if you see what’s happening, it’s rare that you get the chance to change it. For every Martin Luther King or Nelson Mandela there are a million or a hundred million of us who stand idly by, and the creature comforts of Netflix and same-day Prime delivery and did-somebody-say-Just-Eat dull us to the possibilities that we might actually take a stand.

America used to be a beacon of hope and honour and glory.

If the promises of gold-paved streets proved hollow, there was still always a buck to be made for anyone with the energy to go out and make it.

Walt Disney’s people came from Ireland and Canada. Steve Jobs’s birth father was Syrian and his adoptive mother Armenian. Elon Musk came from South Africa at the age of 21.

America was the greatest country in the world, and everyone who wanted to make a better life knew they had to be there.

Is that the same now?

Is it changing?

As men from foreign lands come calling with bigger cheques and deeper pockets, who will be big enough to say no?

That’s it for Part 2