Rory Has a Complex, Crazy Irish Brain. That's The Demon He's Finally Defeated

Ireland has long prided itself on its ability to punch above its weight, especially in music, business and sport. Rory McIlroy's achievement last weekend could be the greatest in the island's history.

An essay on Rory McIlroy, in six short parts.

1. Golf is the world’s greatest game

It’s easy for a lot of people to piss on golf.

Some might point to the fact the game needs the dedicated, even solitary, use of a wide expanse of land at a time when homelessness is rampant, infrastructure is creaking and food production systems are threatened.

Some might suggest the game needs money to get started, and that therefore it is by definition inaccessible and unavailable to a wide cross-section of the population.

Some might say it’s nothing more than a minority sport played by elitists.

I’m biased, of course, but I believe golf is the world’s greatest game.

I believe that because of the way it combines the very best of human vision, ingenuity and engineering and with the very best of God-given nature, environment and time.

2. In this great game, an Irishman has just become an icon

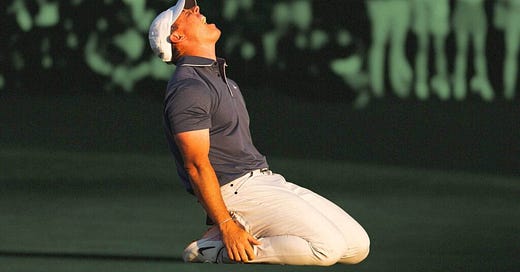

Eleven years in the making, with heartache and heartbreak and psychological torture and several seemingly complete mental meltdowns, McIlroy is now the sixth member of the Career Grand Slam club.

With Tiger Woods, he is the only one to have done it in the past 60 years.

Just think of the greats of those 60 years who haven’t got there.

Nick Faldo. Phil Mickelson. Ernie Els. Lee Trevino.

Tom Watson. Seve Ballesteros. Greg Norman. Bernhard Langer.

It could be a while before anyone becomes the seventh.

Jordan Spieth is just a US PGA away, but how long has it been since he’s been a legitimate contender?

Jon Rahm is halfway there but his form in Majors has tailed off since his move to LIV.

Collin Morikawa and Brooks Koepka likewise have two of the four. Scottie Scheffler, for all his dominance in recent years, has just one of the four Majors.

And while Ireland has long prided itself on its ability to punch above its weight — in business, in music and in sport, we like to measure ourselves against the best anywhere on the planet — the fact is that before Padraig Harrington’s first Open Championship in 2007, the only Irish golfer to win a Major was Fred Daly in 1947.

The past two decades have been a golden era for Irish golf: Graeme McDowell, Darren Clarke, Shane Lowry, Harrington and McIlroy have all won Majors in that time.

For an Irish golfer to win a Major, any Major, is still a massive deal. It could be a long time before Irish people fully digest the fact that one of their own has done what so few have dreamed of, never mind accomplished.

3. Emotional exhaustion

When Rory closed in on his Grand Slam on Sunday, hundreds of thousands of Irish men, women and children stayed up late in the night to see him try.

Those hundreds of thousands of Irish men, women and children weren’t just supporting one of their own.

It’s much more complicated than that.

As a lover of golf, and as an Irishman, this week has been an emotional rollercoaster like no other.

Apart from the emotions of watching someone so clearly emotional try to hold it together in front of a global audience, live and in real time, I’m also exhausted by the magnitude of what all this means.

For me, writing about golf, and the business and money and magic around it.

For Rory McIlroy and his family.

For the game itself.

But maybe most of all, for Ireland.

4. “But is he actually Irish?”

Ireland is an island of around seven million people.

Those seven million are split across two countries, one — the Republic of Ireland — ruled from Dublin, the other, Northern Ireland, with a devolved parliament that sits two hours away in Belfast (I use the word “sits” advisedly; in the first 25 years of this century, the Northern Ireland parliament has been suspended on several occasions for years at a time).

If you’re at one end of Ireland and you leave at first light, you can be at the other end of Ireland in time for an early lunch. (A few years ago there was a story about a university professor who lived in Cork, Ireland’s southernmost county, and worked at Queen’s University Belfast in the north, and how he could drive from his home to the college without meeting a traffic light.)

We are a modern, globalized, cosmopolitan nation now, with vibrant economic success — south of the border, at least — and all the housing and immigration problems that come as a natural offshoot to such success.

The border is invisible now, has been since the Good Friday Agreement of the late 1990s, but despite its invisibility, and despite that invisibility coming under threat by Britain’s Brexit vote in 2016 (which effectively took Northern Ireland out of the European Union while the Republic of Ireland remains one of the EU’s poster-children), the border is still the most significant thing, by far, on our small island.

It was put in place more than a hundred years ago following treaty negotiations in London after the War of Independence. Ever since, this one small island split by a political boundary has been characterized as much as anything else by that fact.

Moments after McIlroy finally sealed the deal on Augusta’s 18th green with the sunlight beginning to fade on Sunday evening, he was gripped in a bear hug by Shane Lowry, his fellow Irishman.

Lowry is from Offaly, in the Republic. McIlroy is from Holywood, in the North.

The two have been Ireland teammates since their amateur days, and while pro golf remains, for the most part, the ultimate individual sport, they are teammates and colleagues still, and the camaraderie, even love, was self-evident in the way McIlroy and Lowry gripped one another beside the Butler Cabin.

But there’s no doubt that when it comes to identity, Lowry’s formative years were simpler than McIlroy’s.

The North-South divide is complicated and difficult.

There are still many people north of the border who see themselves as British first and foremost — a legacy that goes back five centuries to the Ulster plantation and beyond.

In the 2021 Northern Ireland census:

42.8% identified as British, alone or with other national identities.

33.3% identified as Irish, alone or with other national identities.

31.5% identified as Northern Irish, alone or with other national identities.

And yet many of those who see themselves as Irish feel let down by the South.

They see themselves as Irish. They want a 32-county unified country — the kind of ideal that was normal and natural for the freedom fighters of 1916-21, but which, after the border came, brought the decades of war and strife that became somewhat euphemistically known as “The Troubles”.

But they also see that the political leaders in the Republic to the south have chummed it up in Brussels and Berlin and Boston, and left Belfast to fend for itself.

Amongst this, there is hurt, great hurt, and there is fragile identity.

The Monday morning after McIlroy’s win, I met someone and their first question was:

“But is he actually Irish?”

Others, the type of keyboard warriors that ruin online discourse for all of us, accused Rory of “feeling more British than Irish”, or recalled how he didn’t want to take part in the Olympics when golf was brought into the fold in 2016 because of the difficult conversation of which flag he would play for.

You cannot understand Rory McIlroy without understanding this fact.

He is the greatest pro golfer of his generation, probably the greatest sportsperson the island of Ireland has ever produced, but still his identity — how others see him, and perhaps also how he sees himself — is wrapped up in something much more than just golf.

5. Geniuses and madnesses and gods and demons

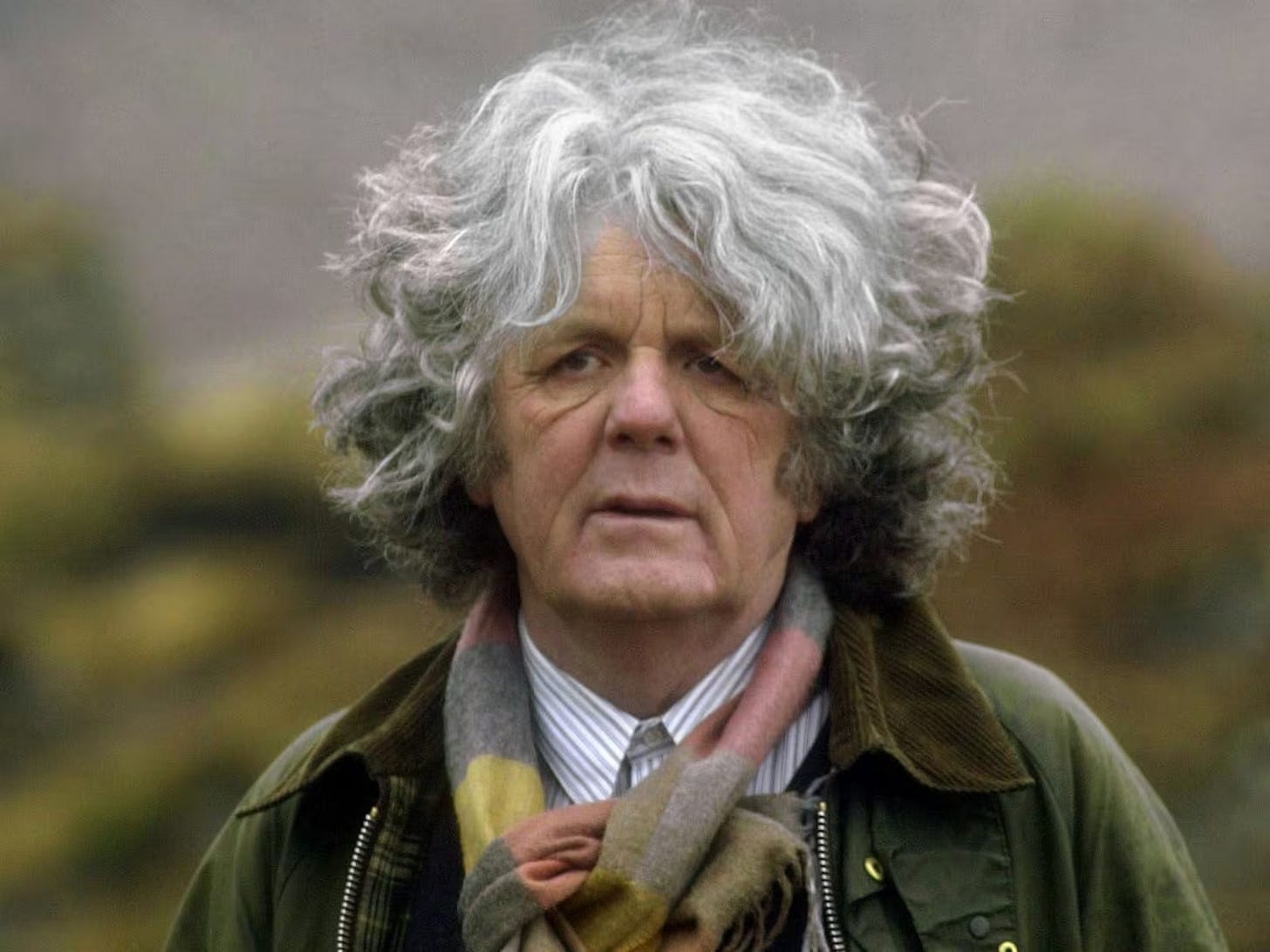

John Moriarty was a great writer and poet and mystic and philosopher who died in 2007.

Moriarty once said that the great tragedy of Ireland came when independence from Britain was achieved and our leaders pursued a standard national entity, that of political nation state.

Moriarty felt that Ireland was different, that Ireland had always been different, going back through tens of thousands of years, of Celtic spirituality and far beyond, to druids and gods and fairy-folk and magic.

Moriarty believed that Ireland’s natural state of being is that of shamanism, an ancient path of wisdom, deep and manifold layers of consciousness and mystical connection to the earth that might date back fifty thousand years or more, and that fully embracing that by declaring Ireland a shamanic state was an opportunity missed by the revolutionaries, rebels and politicians of the 1910s and ‘20s.

This is an indelible part of the magic and mania and madness that courses through Irish people’s veins.

It is, perhaps, the source code for why the greatest of Irish exports include alcoholic drinks and the pubs we drink them in.

Our potential is forever bound up in potions.

Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus were great, no doubt, but in a way they just had to be great at what they were great at.

Rory McIlroy is great, while carrying genes and strands of DNA that sees countless conflicting feelings and identities, geniuses and madnesses, gods and demons rise up in him, like they rise up in Irish people everywhere.

6. Greatness is much more than just achievement

Like nothing else, sport gives the calendar year its milestones and rhythms.

It also gives us a window into the human psyche like no other medium. This is especially so in televised elite sport, where everything is on the line and everyone is watching in real time.

Teddy Roosevelt delivered a great speech in Paris in 1910 that became known as “The Man in the Arena”.

There, he said:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

This is what televised elite sport does. It shows us the man in the arena, live and up close, at the greatest and hardest moments of their existence.

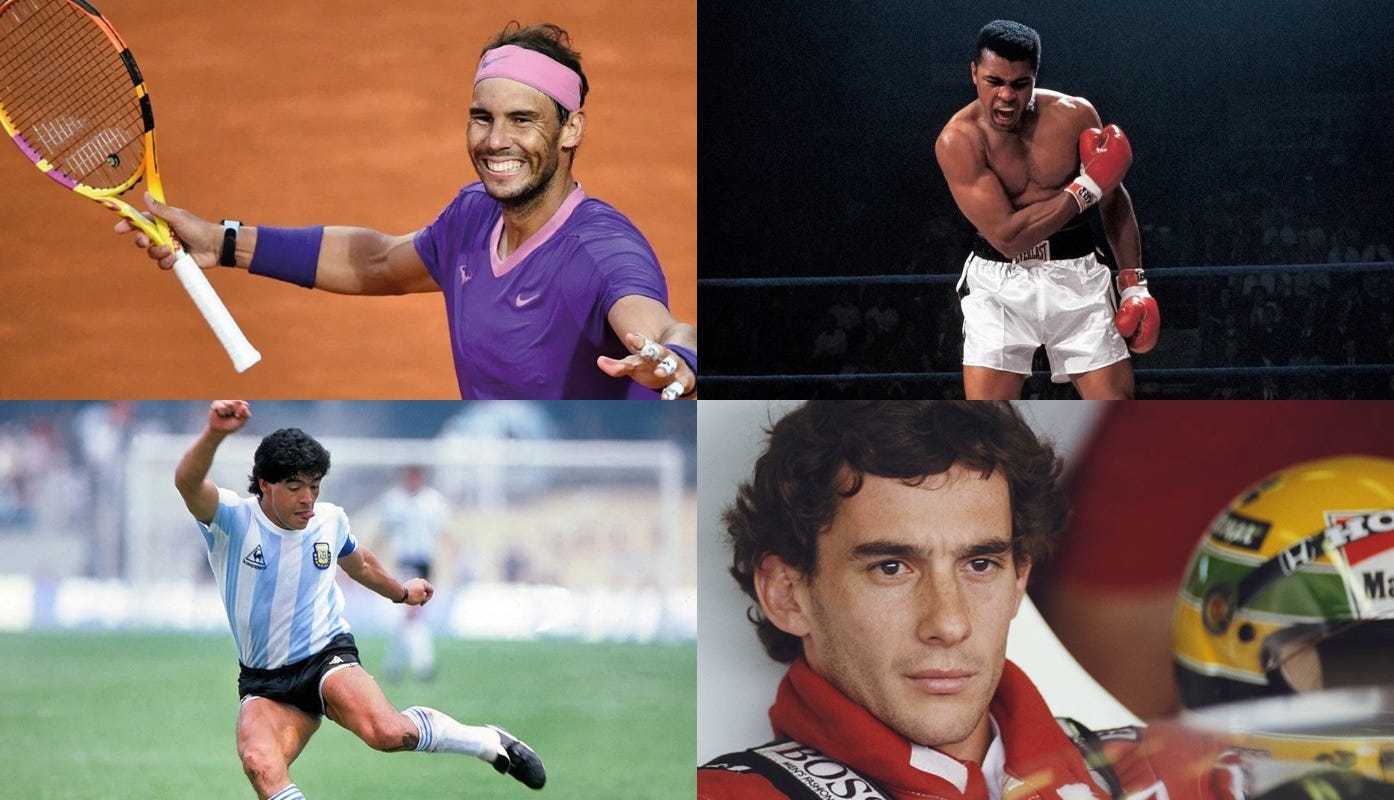

A few years ago, I wrote a short book detailing what I learned about how to be a man from watching the tennis player Rafa Nadal at work.

Nadal, much more than his great contemporaries Djokovic and Federer, is amongst the most interesting sportsmen of all time.

I would count the soccer player Diego Maradona, the boxer Muhammad Ali and the race-driver Ayrton Senna alongside him. All brought an astonishing psychological complexity to their various arenas, and it was this psychological complexity, just as much as what they actually achieved, that made them so compelling.

They were all compelling because of what went on inside their minds, and how that both helped and hindered them in their aim of getting the most out of their bodies.

For years now, McIlroy has been a member of this club.

When he stood over tiny putts at Pinehurst’s 16th and 18th greens in the final round of the US Open last June, trying to end a 10-year wait for a Major championship, the psychological torment he was going through was both completely invisible and wholly palpable.

If that was torture, for him and for all of us who love watching him, it paled in comparison to the torture of his final round at the Masters on Sunday.

In the space of a few minutes, he dunked the ball into the drink from 80 yards at the 13th and then hit one of the greatest shots in the sport’s history at the 15th, all while missing makeable putts at almost every hole on the back nine.

This is, I think, why human beings love watching Rory McIlroy.

We love seeing the heights and depths of what another human is capable of.

We can admire the Tiger Woods of 2000, machine-like and God-like.

But we can love the Tiger Woods of 2019, all aspiration, toil and frailty.

We admired Rory McIlroy when he was streaking to victory in 2012 and 2014.

But the McIlroy that wears all his endless struggles on his sleeve, the McIlroy who’s never comfortable and never lets you get comfortable while you watch, the McIlroy who goes for it even when going for it seems to raise the risk ratio to unacceptable levels, the McIlroy who fought relentless demons inside his own mind and broke down in tears at Augusta when they were finally beaten off…

… that’s a Rory McIlroy we can love.

And no matter what anyone says, love goes a long, long way.

Thanks for reading.

Shane

Superb. So many things in the mix for Rory, so much pressure. It was gladiatorial, and when I heard later that Rory had been delving into the Stoics in order to better face and grow through adversity, it all starts to make sense. Thanks for sharing, Shane!